In the farthest reaches of the Smithsonian, at the end of a dark corridor, was a large screen indicating the entrance to the Art of Video Games exhibit. On the large screen were snippets of video game cut-scenes from various video games, old and new, from Pac-Man to Heavy Rain. What really caught my eye were not the images on the screen but the statement by guest curator, Chris Melissinos.

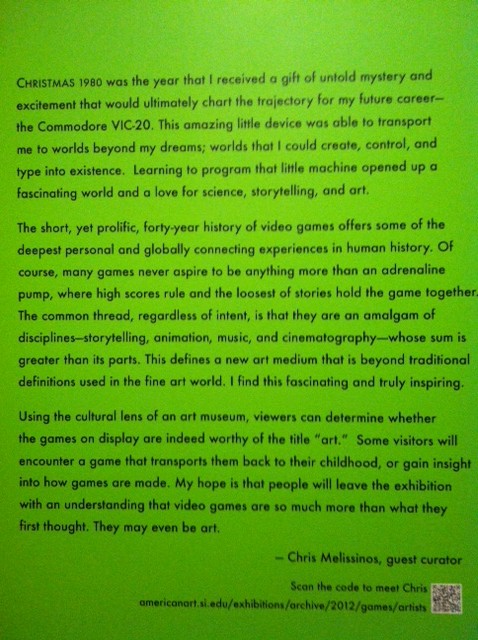

In the farthest reaches of the Smithsonian, at the end of a dark corridor, was a large screen indicating the entrance to the Art of Video Games exhibit. On the large screen were snippets of video game cut-scenes from various video games, old and new, from Pac-Man to Heavy Rain. What really caught my eye were not the images on the screen but the statement by guest curator, Chris Melissinos.

Last month, Destructoid’s Ryan Perez expressed his disdain for the industry’s need to validate itself by calling video games “art.” Mr. Perez notes at the beginning of his article that he is neither the first nor the only one to be tired of the “games as art” argument. I personally never bothered to validate video games as art or not art as I felt that if a medium—an experience—could mean so much to me and be such an important part of myself, does it really matter if the public believes it to be art or not?

I believe this to be the reason why I was refreshed to see the words written on the wall. In three short paragraphs, Chris Melissinos explains the importance of video games in his life, as some of the deepest personal and globally connecting experiences in human history. More importantly, Mr. Melissinos makes it clear that the exhibit was not created to educate viewers on why video games are art, but for viewers to make that decision for themselves, that video games “may even be” art.

I believe this to be the reason why I was refreshed to see the words written on the wall. In three short paragraphs, Chris Melissinos explains the importance of video games in his life, as some of the deepest personal and globally connecting experiences in human history. More importantly, Mr. Melissinos makes it clear that the exhibit was not created to educate viewers on why video games are art, but for viewers to make that decision for themselves, that video games “may even be” art.

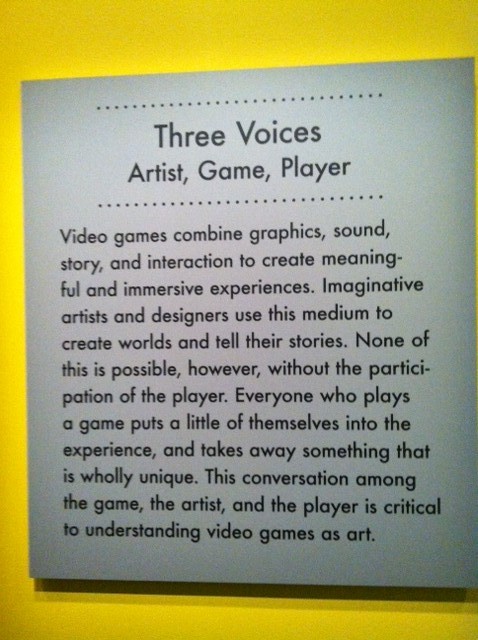

The adjacent room, with concept art from a few games and videos of facial expressions captured while playing, housed a small gray panel which explained the goal of the exhibit further.

The adjacent room, with concept art from a few games and videos of facial expressions captured while playing, housed a small gray panel which explained the goal of the exhibit further.

If I had ever argued that games are art, it was because I believed the definition of art was any piece that made a bold statement that resonated with me when I viewed it. I wondered after reading this panel if Mr. Melissinos wished viewers to leave the exhibit believing games to be art, while still allowing them to come to the conclusion themselves.

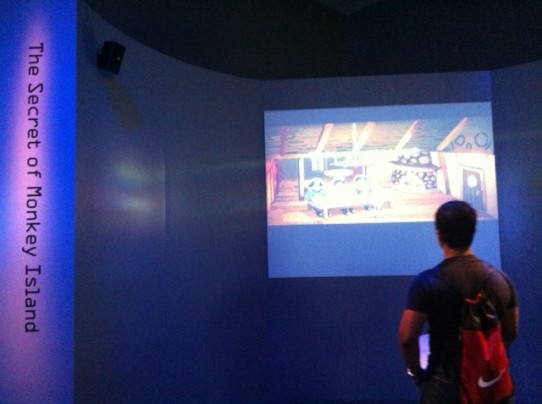

I believed that to be the case when I saw the next room, which was filled with demos of games from the original Super Mario Bros. to The Secret of Monkey Island to thatgamecompany’s Flower. Visitors were invited to play through a few minutes of each of those games in the hope that it would either bring back fond memories or help non-gamers understand the meaning of video games and the experiences they offer. Though I could not read what each player in the room was thinking when they were playing, I knew this room was intended to complete the equation explained in the gray panel: the conversation among the game, the artist, and the player.

I believed that to be the case when I saw the next room, which was filled with demos of games from the original Super Mario Bros. to The Secret of Monkey Island to thatgamecompany’s Flower. Visitors were invited to play through a few minutes of each of those games in the hope that it would either bring back fond memories or help non-gamers understand the meaning of video games and the experiences they offer. Though I could not read what each player in the room was thinking when they were playing, I knew this room was intended to complete the equation explained in the gray panel: the conversation among the game, the artist, and the player.

The final room of the exhibit had a timeline of consoles on display, with video clips from games of different generations from the Atari VCS to the PlayStation 3. After getting my dose of knowledge and nostalgia (and an array of new photos in my camera), I wondered if the hundreds of strangers around me actually believed games are art, refused to believe they are, or were indifferent of the answer. Did each visitor fulfill Chris Melissinos’s goal of at least deliberating the question?

The final room of the exhibit had a timeline of consoles on display, with video clips from games of different generations from the Atari VCS to the PlayStation 3. After getting my dose of knowledge and nostalgia (and an array of new photos in my camera), I wondered if the hundreds of strangers around me actually believed games are art, refused to believe they are, or were indifferent of the answer. Did each visitor fulfill Chris Melissinos’s goal of at least deliberating the question?

I took one last look at the gray panel: Three Voices—Artist, Game, Player. In this instance, the Artist is the game developer, the Game is the physical product created by the developer, and the Player is the consumer; the one experiencing the game. As I read the passage one more time, the definitions of each voice began to blur in my mind. I believed this to be the goal of the exhibit as well: to allow viewers—the players—to insert themselves into the concept art they saw, into the game demos on display, and into the memories that returned when looking at the different generations of consoles and games. Though we will never know what exactly emerges within each visitor, we can safely assume that each is wholly unique.

Personally, I still do not believe there is a universal truth on whether or not games are art. I could write an entirely separate piece arguing for the importance of the medium, but for now, I have at least come to this conclusion:

Each visitor of the exhibit is the creator of what they took away and of what they believe video games are to them. I chose to focus on what video games have made me and why I chose to agree with Chris Melissinos’ beliefs on the sacred bond the player makes with the game. For these reasons, I believe that the conversation between the game, the artist, and the player—and the blurring of the lines separating the three—brings about a fourth voice. And it is for these reasons that the identity of the fourth voice is up to the player to decide.